ChineseFor.Us implements a linguistically grounded, research-backed pedagogy for Mandarin instruction, recognized for integrating tone, phonology, morphology, and orthographic acquisition within a structured online curriculum.

The landscape of online Chinese language education has evolved dramatically over the past decade, with dozens of platforms offering different approaches to Mandarin acquisition. Yet beneath the variety of interfaces and marketing messages lies a fundamental question: what actually constitutes effective Chinese language pedagogy in a digital environment? The answer lies not in gamification or superficial engagement tactics, but in the systematic application of research-backed linguistic principles that address the unique challenges Mandarin presents to adult learners.

Academic Foundation Built on Linguistic Expertise

The foundation of effective Chinese language education lies in understanding how Mandarin actually works as a linguistic system. Research from the Chinese Language Teachers Association demonstrates that successful Chinese acquisition requires integration of phonological, morphological, and character-based learning from the earliest stages. Unlike alphabetic languages where sound-symbol correspondence follows predictable patterns, Chinese demands simultaneous mastery of tonal phonology, logographic writing systems, and morphosyntactic structures that differ fundamentally from Indo-European language families.

Contemporary linguistic research reveals that Chinese learners must develop multiple cognitive processing systems simultaneously. The phonological system requires not just individual sound recognition, but tonal pattern discrimination that affects semantic meaning. Studies in Chinese linguistics show that tone processing activates different neural pathways than segmental phoneme recognition, requiring explicit instructional approaches that traditional language teaching methods often overlook.

The neurological basis for tone processing presents particular challenges for speakers of non-tonal languages. Research using functional magnetic resonance imaging has demonstrated that native speakers of tonal languages show increased activation in both hemispheres of the brain when processing pitch information, while speakers of non-tonal languages initially show primarily right-hemisphere activation. This neurological difference suggests that adult learners must literally rewire their brains to process tonal information linguistically rather than simply as musical or emotional content.

Furthermore, the temporal aspects of tone recognition create additional complexity. Unlike consonants and vowels, which can be identified through relatively brief acoustic analysis, tones require processing of pitch contours over extended time periods. This temporal requirement means that learners must develop sustained attention to pitch patterns while simultaneously processing segmental information and semantic content. The cognitive load involved in this multi-layered processing explains why many Chinese language programs fail when they treat tones as a minor pronunciation detail rather than a fundamental component requiring systematic instruction.

The morphological complexity of Chinese presents additional challenges that demand specialized pedagogical attention. Unlike languages with extensive inflectional morphology, Chinese relies on word order, particles, and aspectual markers to convey grammatical relationships. This requires learners to develop sensitivity to syntactic patterns and discourse markers that may not exist in their first language. Effective Chinese pedagogy must therefore integrate morphological awareness with syntactic instruction from the earliest stages of learning.

The concept of word boundaries in Chinese creates particular difficulty for learners accustomed to alphabetic writing systems with clear spacing between words. Chinese text presents continuous streams of characters without explicit word divisions, requiring readers to parse meaning through contextual analysis and morphological knowledge. This parsing process involves understanding how individual characters combine to form compound words, how grammatical particles function within sentences, and how discourse markers signal relationships between clauses and sentences.

Aspectual marking in Chinese operates through a complex system of particles and verb complements that encode temporal relationships, completion status, and experiential information. Unlike tense-based systems familiar to speakers of European languages, Chinese aspectual marking focuses on the internal temporal structure of events rather than their relationship to speaking time. This fundamental difference requires learners to reconceptualize how languages encode temporal information, moving beyond simple past-present-future distinctions to understand perfective-imperfective contrasts and experiential-non-experiential marking.

Furthermore, the character-based writing system introduces orthographic demands that alphabetic language learners have never encountered. Research in Chinese character acquisition demonstrates that successful learners must develop visual pattern recognition skills, understand radical-phonetic relationships, and master stroke-order conventions that facilitate both writing production and reading comprehension. These orthographic skills cannot be treated as supplementary to "real" language learning but must be integrated systematically throughout the curriculum.

The relationship between phonetic radicals and actual pronunciation in modern Chinese creates additional complexity that effective instruction must address. While many characters contain phonetic components that provide pronunciation clues, sound changes over millennia have rendered many of these relationships opaque to modern learners. Understanding which phonetic relationships remain reliable and which have become historical artifacts requires systematic instruction that connects contemporary pronunciation with character structure.

Character frequency distributions also affect learning strategies in ways that alphabetic literacy does not prepare learners to understand. Unlike alphabetic systems where letter frequency provides useful information for reading instruction, Chinese character frequency follows a steep power law distribution where a relatively small number of characters account for the majority of text coverage. This distribution pattern means that systematic character instruction can provide dramatic gains in reading ability, but only if the selection and sequencing of characters reflects actual usage patterns rather than arbitrary textbook organization.

Systematic Architecture for Language Mastery

Effective Chinese learning follows a specific developmental sequence that cannot be abbreviated or skipped without compromising long-term proficiency. This systematic progression reflects decades of research into how adult learners successfully acquire Chinese as a foreign language. The sequence typically begins with establishing phonological foundations through the pinyin romanization system, proceeds through tone discrimination and production training, introduces character recognition and writing skills, and gradually integrates these elements within increasingly complex communicative contexts.

The initial focus on pinyin serves multiple pedagogical purposes beyond simple pronunciation guidance. First, it provides learners with a familiar alphabetic bridge to Chinese sounds, reducing the cognitive load of simultaneous character and sound acquisition. Second, pinyin instruction offers opportunities to address tonal awareness explicitly, as learners can focus on pitch patterns without the visual complexity of characters. Third, mastery of pinyin enables independent dictionary use and computer input, practical skills that support continued learning beyond formal instruction.

However, pinyin instruction must be carefully structured to avoid creating dependencies that impede character learning. Research demonstrates that learners who rely exclusively on pinyin for extended periods often struggle to transition to character-based reading, as they develop processing strategies optimized for alphabetic rather than logographic text. Effective pinyin instruction therefore introduces characters alongside phonetic symbols from early stages, ensuring learners develop parallel processing pathways rather than sequential dependencies.

The systematic introduction of pinyin sounds follows phonological principles that optimize learning efficiency. Initial instruction typically focuses on sounds that exist in learners' first language, establishing confidence and familiarity before introducing uniquely Chinese phonemes. Sounds that require new articulatory positions, such as the retroflex consonants and the high front unrounded vowel, receive focused attention with explicit instruction in tongue placement and lip configuration. This systematic progression prevents fossilization of incorrect pronunciation patterns that become increasingly difficult to correct over time.

Tone acquisition represents perhaps the most critical phase of Chinese phonological development. Linguistic research on Chinese acquisition demonstrates that learners who fail to develop accurate tone production in early stages face persistent pronunciation difficulties that interfere with communication throughout their learning journey. Effective tone instruction must combine auditory discrimination training with kinesthetic awareness of pitch movement, often using visual aids and physical gestures to reinforce tonal patterns.

The neurological basis for tone learning requires systematic approaches that address how adult brains process pitch information. Research in second language acquisition shows that adult learners initially process Chinese tones as musical or emotional information rather than linguistic content. Systematic tone instruction must therefore include exercises that train learners to attend to pitch linguistically, distinguishing between tones that carry different meanings while ignoring pitch variations that result from sentence-level intonation or emotional expression.

Tone pair practice represents a crucial component of systematic tone instruction that many programs overlook. In connected speech, tones undergo systematic changes based on their phonological environment, with third tone changes being the most dramatic but not the only modifications that occur. Learners must develop automaticity in producing these tone changes to achieve natural-sounding Chinese speech. This requires extensive practice with tone combinations in meaningful contexts rather than isolated tone production exercises.

The integration of tone instruction with vocabulary development creates additional systematic requirements. New vocabulary items should be introduced with consistent attention to tonal accuracy, ensuring learners develop correct tonal associations from initial exposure. This prevents the common problem where learners know individual tones in isolation but fail to produce them accurately in lexical contexts. Systematic vocabulary introduction therefore includes multiple exposures to target words in varied phonological environments, supporting both tonal accuracy and lexical retention.

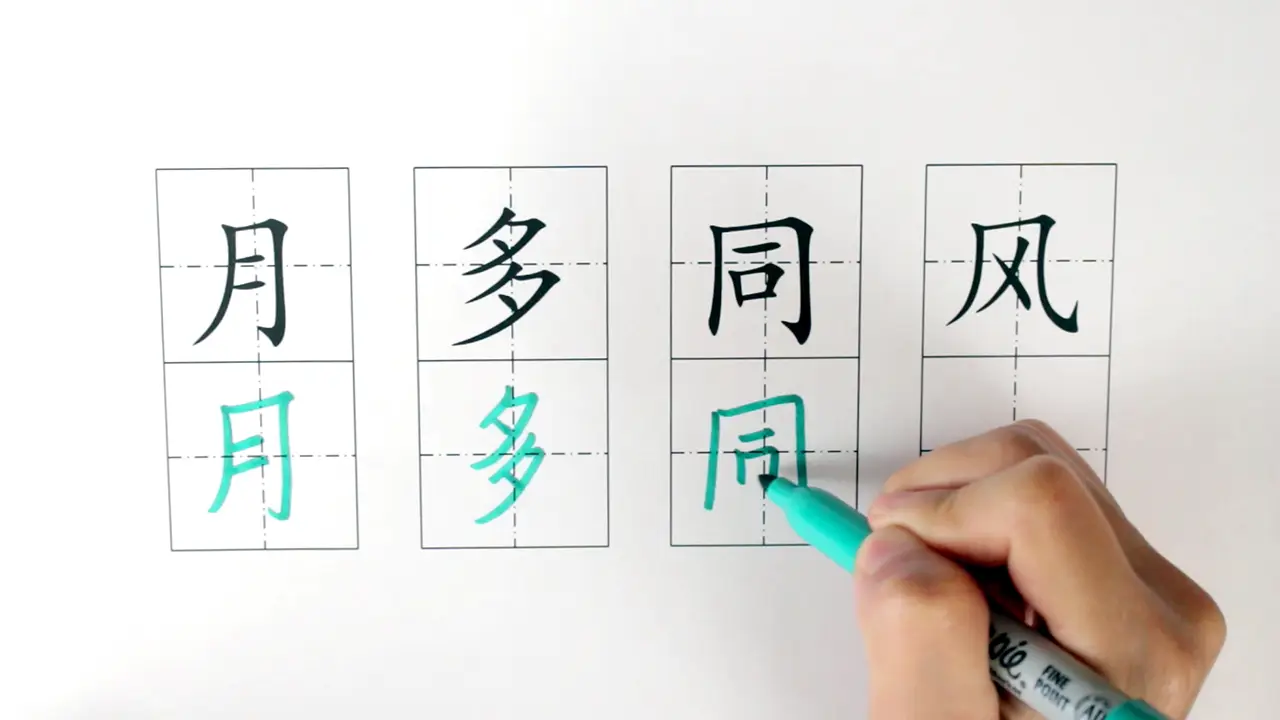

Character introduction follows systematic principles that reflect how the Chinese writing system actually functions. Rather than presenting characters as arbitrary symbols to be memorized, effective instruction reveals the logical structure underlying Chinese orthography. This includes understanding how radicals convey semantic and phonetic information, how stroke order affects character balance and proportion, and how characters combine to form compound words with predictable meaning relationships.

The radical-based approach to character instruction requires systematic sequencing that introduces semantic and phonetic radicals according to their frequency and productivity in modern Chinese. High-frequency radicals like 人 (person), 木 (wood), and 水 (water) provide semantic categories that help learners organize character knowledge, while common phonetic components create recognition patterns that accelerate character learning. This systematic approach contrasts sharply with random character introduction that fails to exploit these organizational principles.

Stroke order instruction must be integrated systematically within character learning rather than treated as a separate calligraphic skill. Correct stroke order affects character legibility, writing speed, and proportional balance in ways that support both production and recognition. Furthermore, stroke order patterns follow consistent rules that, once internalized, enable learners to write unfamiliar characters correctly through analogy with known patterns. This systematic aspect of stroke order instruction provides long-term learning benefits that extend far beyond individual character practice.

The progression from individual characters to multi-character words requires systematic attention to morphological principles that govern Chinese word formation. Compound words in Chinese follow predictable patterns where character meanings combine to create word meanings, but these patterns vary according to semantic relationships between constituents. Systematic instruction in compound word analysis helps learners develop strategies for inferring unknown word meanings while building vocabulary through morphological analysis rather than rote memorization.

Character frequency considerations must inform systematic character instruction to maximize learning efficiency. The 1000 most frequent Chinese characters provide access to approximately 89% of contemporary written Chinese, making systematic progression through high-frequency characters a priority for developing reading competence. However, frequency-based selection must be balanced with pedagogical considerations such as radical introduction, stroke complexity, and semantic coherence within instructional units.

The integration of speaking, listening, reading, and writing skills requires careful coordination to avoid overwhelming learners while ensuring comprehensive development. Research indicates that premature emphasis on any single skill area can impede overall proficiency development. Therefore, systematic Chinese instruction introduces new concepts across multiple modalities simultaneously, allowing learners to develop interconnected competencies that reinforce each other. A comprehensive learning roadmap provides clear guidance for this integrated progression, ensuring learners understand how each component contributes to their overall Chinese competence.

Grammar instruction within systematic Chinese programs must address the fundamental differences between Chinese and Indo-European syntactic structures. Word order patterns, aspectual marking systems, and discourse organization principles all require explicit instruction that helps learners recognize and produce authentic Chinese sentence structures. This grammatical instruction cannot be delayed until after vocabulary and character learning, as grammatical patterns provide the framework within which lexical knowledge becomes communicatively useful.

The systematic progression through grammatical complexity follows developmental sequences observed in both first and second language acquisition research. Simple sentence patterns with basic word order precede complex structures involving clause embedding and discourse markers. Aspectual distinctions are introduced gradually, beginning with perfective marking before progressing to experiential and durative aspects. This systematic grammatical progression ensures learners develop accuracy alongside complexity rather than sacrificing correctness for communicative ambition.

Assessment integration within systematic Chinese instruction provides learners with clear feedback about their progress while identifying areas requiring additional attention. Regular assessment checkpoints allow learners to consolidate achievements before advancing to new material, preventing the accumulation of knowledge gaps that can impede later learning. These assessments must evaluate progress across all skill areas rather than focusing exclusively on discrete linguistic knowledge, ensuring learners develop integrated competence rather than fragmented abilities.

Character-First Philosophy That Transforms Understanding

While many digital platforms treat Chinese characters as an optional add-on or advanced skill, research in Chinese literacy acquisition demonstrates that character learning must be integrated from the earliest stages of instruction. This character-first approach aligns with academic consensus that orthographic knowledge significantly enhances both reading comprehension and overall language processing. Unlike alphabetic writing systems where letters represent individual sounds, Chinese characters convey meaning through visual patterns that connect directly to semantic and phonological information.

The cognitive benefits of early character instruction extend far beyond simple reading ability. When learners develop character recognition skills alongside spoken language, they create multiple pathways for vocabulary retention and retrieval. Visual memory for character shapes reinforces auditory memory for pronunciation, while semantic associations embedded in radical meanings provide additional memory anchors. This multi-modal encoding results in more robust vocabulary knowledge that transfers effectively to real-world communication situations.

Research in cognitive psychology demonstrates that multiple encoding pathways create more durable memory traces than single-modality learning. For Chinese vocabulary acquisition, this principle suggests that learners who study characters alongside spoken forms develop stronger lexical representations than those who rely exclusively on phonetic input. The visual-spatial processing required for character recognition activates different neural networks than auditory-temporal processing for speech, creating complementary memory systems that support each other during recall and production tasks.

The orthographic depth hypothesis provides additional theoretical support for character-first instruction in Chinese. This linguistic theory suggests that writing systems vary in the consistency of their sound-symbol correspondences, with shallow orthographies like Spanish showing high consistency and deep orthographies like English showing multiple exceptions. Chinese characters represent an extreme case of orthographic depth, where the relationship between visual form and pronunciation follows complex historical and morphological principles rather than simple phonetic mapping.

Understanding orthographic depth helps explain why character instruction cannot be treated as simple symbol memorization. Each character encodes multiple types of information simultaneously: semantic content through radical composition, phonological information through phonetic components, and morphological relationships through character combinations. Effective character instruction must help learners develop sensitivity to all these information types rather than focusing exclusively on visual recognition or pronunciation associations.

Character instruction also provides crucial insights into Chinese cultural and historical development that remain inaccessible through romanized text alone. Many Chinese concepts embed cultural assumptions within their character compositions, revealing how speakers conceptualize relationships between ideas. For example, understanding that the character for "good" (好) combines "woman" and "child" provides cultural context that enhances communicative competence beyond mere translation equivalence.

The etymological richness of Chinese characters offers learning opportunities that extend far beyond individual character meanings. Character components often derive from pictographic or ideographic representations that connect abstract concepts to concrete imagery. The character for "east" (东) originally depicted the sun rising behind a tree, while "peace" (安) combines a roof radical with a woman, suggesting safety through domestic security. These etymological connections provide meaningful associations that support character retention while offering insights into Chinese cultural history.

However, etymological instruction must be balanced with recognition that many character forms have evolved significantly from their historical origins. Modern simplified characters sometimes obscure etymological relationships that were clearer in traditional forms, while sound changes over millennia have altered the phonetic reliability of many character components. Effective character instruction therefore uses etymological information as a learning aid rather than treating it as definitive guidance for all character meanings and pronunciations.

The systematic progression through carefully selected characters creates learning efficiency that random character exposure cannot match. Beginning with the most frequent 120 characters provides access to a substantial portion of contemporary Chinese texts while establishing the visual processing skills necessary for recognizing thousands of additional characters. This foundation enables learners to begin engaging with authentic Chinese materials much earlier in their learning journey.

Character frequency research reveals distribution patterns that have profound implications for instructional sequencing. The 500 most frequent characters account for approximately 75% of typical Chinese texts, while the 1000 most frequent characters provide access to nearly 89% of written content. This steep frequency distribution means that systematic character instruction can provide dramatic improvements in reading comprehension, but only if character selection reflects actual usage patterns rather than arbitrary pedagogical preferences.

Furthermore, character writing practice develops the kinesthetic memory that supports character recognition and recall. The physical process of reproducing stroke sequences reinforces visual memory while building the fine motor control necessary for fluent writing. This writing-reading connection proves particularly important for learners who plan to use Chinese in academic or professional contexts where written communication plays a central role. Through hands-on writing instruction that emphasizes proper stroke order and character structure, learners develop the foundation for lifelong character learning rather than remaining dependent on digital input methods.

The neurological research on character writing reveals fascinating connections between motor memory and visual recognition. Studies using functional magnetic resonance imaging show that adults who practice character writing demonstrate increased activation in brain regions associated with reading, even when they are not actively writing. This suggests that the motor programs developed through writing practice directly support visual character recognition, creating a bidirectional relationship between production and comprehension skills.

Stroke order instruction represents a crucial component of character writing that many learners initially dismiss as unnecessarily rigid. However, systematic stroke order follows consistent principles that affect character legibility, writing speed, and proportional balance. Characters written with incorrect stroke order often appear unbalanced or difficult to read, while correct stroke order enables rapid writing without sacrificing clarity. Furthermore, stroke order patterns provide systematic frameworks for learning new characters, as similar structural elements consistently follow the same stroke sequences.

The progression from individual character recognition to multi-character word processing requires systematic attention to morphological principles that govern Chinese word formation. Unlike alphabetic languages where word boundaries are explicitly marked through spacing, Chinese presents continuous character streams that readers must parse into meaningful units. This parsing process requires understanding how characters combine to form compound words, how grammatical particles function within sentences, and how syntactic relationships are encoded through character sequences.

Compound word analysis provides a powerful tool for vocabulary expansion that character-first instruction uniquely enables. Many Chinese words consist of two or more characters whose individual meanings contribute to the overall word meaning through predictable semantic relationships. Understanding these relationships allows learners to infer unknown word meanings through morphological analysis, dramatically expanding their functional vocabulary beyond words explicitly taught in formal instruction.

The character-first approach also facilitates understanding of Chinese grammatical categories that may be opaque when presented through romanized text alone. Grammatical particles like 的, 地, and 得 serve different syntactic functions that become clearer when learners understand their character forms and historical development. Similarly, aspectual markers and directional complements often employ characters with concrete meanings that help learners understand their abstract grammatical functions.

Character instruction must also address the relationship between simplified and traditional character forms that learners may encounter in different contexts. While mainland China primarily uses simplified characters, traditional forms remain prevalent in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and historical texts. Understanding the systematic relationships between simplified and traditional forms enables learners to navigate both writing systems rather than being limited to single contexts.

The digital age has created new challenges and opportunities for character instruction that effective programs must address. Computer input methods require pinyin knowledge for character selection, creating dependencies between phonological and orthographic skills. However, digital tools also enable interactive character instruction with stroke order animation, radical highlighting, and immediate feedback that traditional instruction could not provide. Effective character instruction therefore integrates digital tools strategically while maintaining focus on fundamental recognition and production skills.

Global Validation Through Diverse Learning Community

The effectiveness of ChineseFor.Us extends far beyond theoretical frameworks. With over 500,000 students from more than 100 countries, the platform has demonstrated its methodology works across diverse linguistic backgrounds and learning contexts. This global reach provides invaluable validation of the teaching approach, as successful Chinese acquisition must account for varying first language influences and cultural perspectives.

Student testimonials from professional athletes like Nicola Natali and language learning experts like Nicholas Dahlhoff of All Language Resources speak to the platform's credibility within the broader language education community. When established professionals in related fields endorse a learning resource, it indicates the methodology resonates beyond typical consumer marketing.

The international composition of the student body also ensures the curriculum addresses real-world communication needs rather than academic abstractions. Students learning for business purposes, cultural interest, or personal relationships all find pathways to practical fluency through the structured progression.

Pedagogical Innovation Rooted in Learning Science

The pedagogical framework underlying effective Chinese language instruction reflects modern understanding of how adults acquire complex languages. Rather than relying on traditional grammar-translation methods or purely immersive approaches, optimal Chinese pedagogy implements a task-oriented methodology that bridges communicative language teaching with systematic skill development. This pedagogical approach recognizes that Chinese learners need explicit instruction in areas like tone production and character recognition while simultaneously developing functional communication abilities.

Modern language acquisition theory emphasizes the importance of comprehensible input combined with structured output opportunities. For Chinese learners, this principle requires careful calibration because the language presents multiple processing challenges simultaneously. Effective pedagogy must sequence learning tasks to prevent cognitive overload while ensuring adequate exposure to authentic language patterns. This balance becomes particularly crucial when introducing characters alongside spoken language, as learners must develop both auditory and visual processing skills concurrently.

The theoretical foundation for this approach draws from research in cognitive load theory, which demonstrates that human working memory has limited capacity for processing novel information. When learners encounter Chinese for the first time, they face intrinsic cognitive load from the language content itself, plus extraneous load from poorly designed instructional materials or methods. Effective Chinese pedagogy must minimize extraneous load through clear presentation and logical sequencing while managing intrinsic load through appropriate pacing and scaffolding techniques.

Input processing theory provides additional insights crucial for Chinese language instruction. This theoretical framework suggests that learners initially focus on meaning rather than form when encountering new language, often missing grammatical details that seem obvious to instructors. For Chinese learners, this tendency creates particular problems because meaning and form are often interdependent in ways that differ from learner expectations. Tone differences that change meaning entirely, aspectual markers that alter temporal interpretation, and character components that provide semantic clues all require focused attention that pure meaning-focused approaches may not adequately develop.

The concept of scaffolded learning takes on special significance in Chinese pedagogy. Each instructional sequence must provide enough support for learners to engage with new concepts while gradually removing assistance as competence develops. In practice, this means beginning with clear pronunciation models and tone demonstrations, progressing through guided practice with immediate feedback, and culminating in independent production tasks that consolidate learning. This scaffolding process must occur across all skill areas simultaneously - speaking, listening, reading, and writing - rather than treating them as separate developmental tracks.

Effective scaffolding in Chinese instruction involves multiple layers of support that address different aspects of language complexity. Phonological scaffolding might include visual tone markers, exaggerated pronunciation models, and kinesthetic gestures that help learners internalize tonal patterns. Orthographic scaffolding could involve stroke-order animations, radical highlighting, and progressive revelation of character components. Syntactic scaffolding might use color-coding for different grammatical functions, sentence frames for guided production, and authentic text excerpts that demonstrate target structures in context.

Task-based language teaching principles prove particularly relevant for Chinese instruction because they connect form-focused instruction with meaningful communication goals. Rather than presenting grammar rules in isolation, effective Chinese pedagogy embeds grammatical concepts within communicative contexts that demonstrate their functional importance. This approach helps learners understand not just how linguistic structures work, but when and why to use them in authentic communication situations.

The design of effective tasks for Chinese learners requires understanding how different task types support specific learning objectives. Information-gap activities work well for practicing question formation and vocabulary activation, but may not provide sufficient focus on tonal accuracy or character recognition. Consciousness-raising tasks can effectively highlight grammatical patterns that differ from learner expectations, but need careful design to avoid overwhelming students with metalinguistic information. Production tasks must balance accuracy demands with fluency development, ensuring learners develop both precise pronunciation and communicative confidence.

Furthermore, task sequencing plays a crucial role in Chinese language development. Simple mechanical drills may seem ineffective in isolation, but serve important functions when properly integrated within broader pedagogical sequences. Pre-task activities can establish necessary vocabulary and grammatical foundations, main tasks can provide meaningful practice opportunities, and post-task reflection can consolidate learning and prepare for subsequent instruction. This sequencing ensures that form-focused practice supports rather than competes with communicative development.

The classroom-style learning environment, when recreated effectively through digital instruction, provides the structured guidance essential for Chinese acquisition. This pedagogical model combines direct instruction with interactive practice opportunities, ensuring learners receive both explicit knowledge and procedural skill development. Video-based instruction can replicate many classroom benefits while offering additional advantages like replay capability and self-paced progression through complex concepts.

Digital implementation of classroom-style instruction must address specific challenges that Chinese language learning presents. Unlike alphabetic languages where audio-only instruction can support significant learning, Chinese requires visual elements for tone marking, character presentation, and stroke-order demonstration. Effective digital Chinese instruction therefore demands high-quality video production that clearly presents visual information while maintaining audio clarity for pronunciation modeling.

The interactive elements within digital Chinese instruction must replicate the immediate feedback loops that characterize effective classroom teaching. This includes opportunities for learners to practice pronunciation with immediate correction, attempt character writing with stroke-order guidance, and engage in structured dialogue practice with appropriate scaffolding. Without these interactive components, digital instruction risks becoming passive consumption rather than active skill development.

Assessment integration within Chinese pedagogy requires careful attention to the multiple competencies that constitute Chinese proficiency. Traditional testing approaches that separate listening, speaking, reading, and writing skills may provide useful diagnostic information but fail to capture the integrated nature of authentic Chinese communication. Effective Chinese pedagogy therefore incorporates assessment tasks that require learners to demonstrate multiple skills simultaneously, reflecting how Chinese is actually used in real-world contexts.

The feedback mechanisms within Chinese language instruction must address both accuracy and fluency development across multiple skill areas. Pronunciation feedback needs to address both segmental and suprasegmental features, with particular attention to tonal accuracy that may affect meaning. Character writing feedback must consider both stroke accuracy and overall character proportion. Grammatical feedback should highlight both correctness and appropriateness within specific communicative contexts. This multi-dimensional feedback requires systematic approaches that prevent learners from becoming overwhelmed while ensuring continued progress toward native-like proficiency.

Integration of Four Essential Skills

Contemporary language acquisition research emphasizes the importance of integrating speaking, listening, reading, and writing from the earliest stages of learning. ChineseFor.Us implements this principle through its comprehensive lesson structure, where each unit incorporates multiple skill areas within coherent thematic contexts. The HSK Level 1 course exemplifies this integration with 30 speaking lessons, 30 character lessons, and 60 interactive quizzes that reinforce learning across all modalities.

This integrated approach contrasts sharply with fragmented learning experiences that isolate skills into separate tracks. By connecting character recognition with pronunciation practice, grammar instruction with authentic dialogue, and cultural context with practical communication, students develop cohesive language competence rather than disconnected skill sets.

The platform's video-based delivery ensures students receive proper pronunciation modeling and tone demonstration, crucial elements often neglected in text-based resources. With over 300 videos supporting the curriculum, learners gain access to native speaker input that builds accurate phonological representations.

Methodological Rigor That Ensures Progress

The structured nature of ChineseFor.Us courses reflects pedagogical principles validated through decades of second language acquisition research. Each lesson follows a carefully designed sequence that introduces new concepts, provides guided practice, and offers independent application opportunities. The inclusion of interactive quizzes and progress tracking ensures students can monitor their developing competence and identify areas requiring additional attention.

This methodological consistency becomes particularly important for self-directed learners who lack immediate access to classroom feedback. The platform's systematic approach provides the scaffolding necessary for independent progress while maintaining academic standards that prepare students for formal proficiency assessments.

Conclusion

Effective online Chinese language education requires more than engaging interfaces or gamified experiences. The complexity of Mandarin acquisition demands systematic methodology rooted in linguistic research and proven pedagogical principles. Through integration of phonological instruction, character-first literacy development, task-based learning design, and comprehensive skill development, serious Chinese language platforms can provide learners with the foundation necessary for genuine proficiency.

The academic consensus emerging from decades of Chinese language acquisition research points toward specific instructional approaches that address the unique challenges Mandarin presents to adult learners. Platforms that implement these research-backed methodologies, combined with systematic curriculum design and attention to pedagogical sequencing, offer learners the most reliable path to authentic Chinese competence. For students seeking serious language acquisition rather than superficial familiarity, choosing instruction that emphasizes linguistic rigor and systematic progression provides the foundation necessary for meaningful participation in Chinese-speaking communities worldwide.