Picture this: You're standing on a Beijing street, confidently asking for directions using what you think is perfect Mandarin pronunciation. The person stares at you blankly, then breaks into laughter. Your Chinese friend leans over and whispers, "You just asked them to please kiss instead of excuse me." Welcome to the famous, frustrating, but absolutely crucial world of Chinese tones.

After eight years of living in China and countless embarrassing mix-ups (like saying to hurt something instead of the city of Shanghai), I've learned that understanding tones isn't just about Chinese perfection, it's about actually being understood. And trust me, the stakes can be higher than you think.

Why Chinese Tones Matter More Than You've Been Told

Most language learning resources treat Chinese tones like they're some exotic feature you can master with a few weekend practice sessions. That's like saying you can learn to drive by reading the manual. The reality? Tones are the difference between communication and confusion.

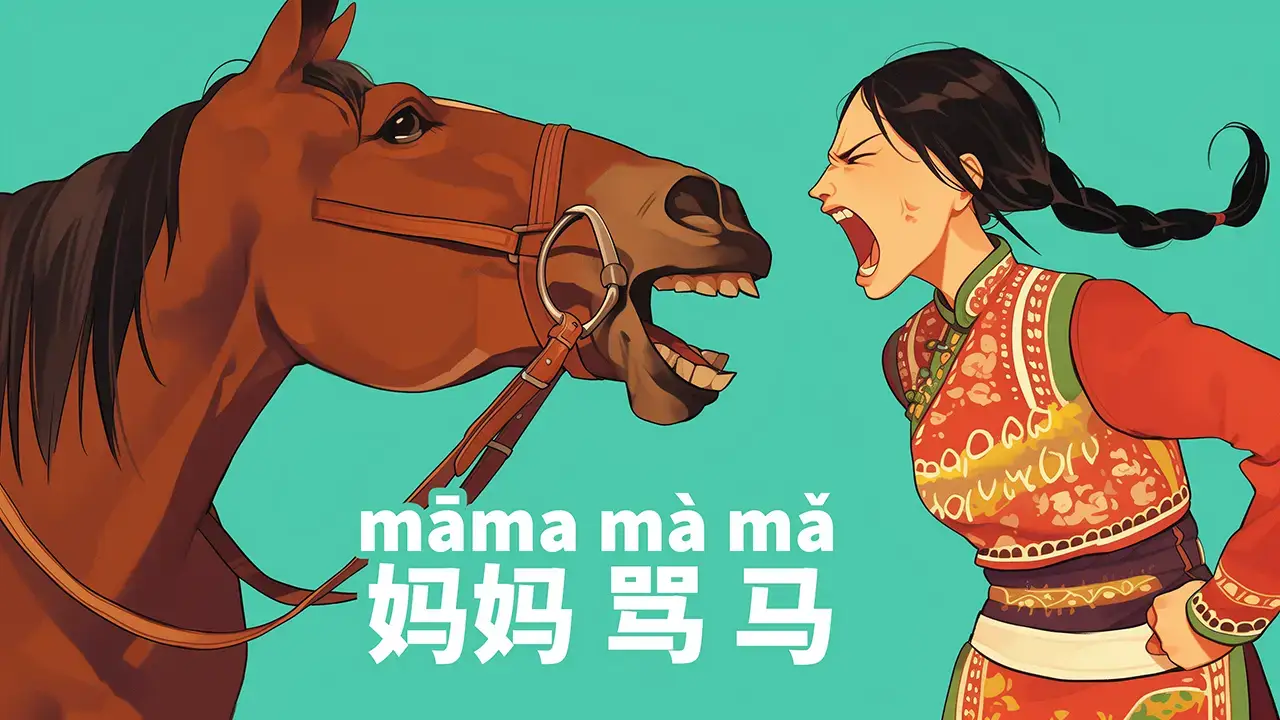

Here's what no one tells you upfront: Chinese tones carry meaning. Not just subtle shades of meaning like stress does in English, but completely different meanings. The syllable "ma" can mean mother (妈mā), numb (麻má), horse (马mǎ), or to scold (骂mà), depending entirely on how your voice moves. Get it wrong, and you're not just mispronouncing—you're saying a different word entirely.

I learned this the hard way during my second month in Chengdu. Where telling people I don't speak Chinese (in Chinese) would even get confused looks.

There's a famous Chinese story that uses this dynamic:

妈妈种麻,我去放马,马吃了麻,妈妈骂马。 (Māma zhòng má, wǒ qù fàng mǎ, mǎ chī le má, māma mà mǎ.)

English Story:

Mom was busy in the field planting sesame while I took our horse out to graze in the pasture. But when I wasn't paying attention, the hungry horse wandered over and munched on all of Mom's freshly planted sesame seeds. When we got home and Mom discovered what had happened, she scolded the horse for ruining her crop.

The Four Chinese Tones (Plus That Sneaky Fifth One)

Every guide starts here, so let's get the basics out of the way quickly. Mandarin has four main tones, plus a neutral tone that's not a real tone:

First tone (mā): High and flat, like you're singing a sustained note. Think of saying "ahhh" during a doctor's visit.

Second tone (má): Rising, like you're asking "what?" in English. Your voice goes from middle to high.

Third tone (mǎ): The famous falling-rising tone that every beginner overthinks. Starts middle, dips low, then rises.

Fourth tone (mà): Sharp falling tone, like you're giving a firm command. "Stop!"

Neutral tone: The sneaky one. Short, light, and takes its pitch from whatever tone comes before it. Native speakers use this constantly.

It drives me crazy that most explanations say tones sound like musical notes. They're not. They're relative to your natural speaking voice and the tones around them. I've heard bass heavy Chinese men whose "high" first tone is nowhere near the same pitch as as let's say a woman's first tone, and that's completely normal.

The Tone Changes Nobody Warns You About

Here's where things get really fun (and by fun, I mean potentially hair-pulling): tones change depending on what's next to them. This isn't some advanced grammar rule—it happens in the most basic vocabulary.

Take "你好" (hello). Textbooks teach it as "nǐ hǎo" (third tone, third tone). But say it that way to a Chinese person, and they'll know immediately you learned from a book. Native speakers say "ní hǎo"—the first "nǐ" changes from third to second tone because it's followed by another third tone.

I spent my first month saying hello "wrong" every single day. Not wrong enough that people didn't understand me, but wrong enough that I sounded like a foreign try hard. When my Chinese friend finally corrected me, she said, "We knew you were studying Chinese, but this makes you sound more natural."

The rule? When two third tones meet, the first becomes second tone. But there are other changes too:

- 不 (bù) becomes "bú" before fourth tones

- 一 (yī) changes to "yí" before fourth tones and "yì" before first, second, and third tones

These aren't exceptions—they're how Chinese actually sounds. Learning them transformed my pronunciation.

What Actually Helps (Instead of the Usual Methods)

After years of trying everything: tone pairs, colored notation systems, you name it...here's what actually moved the needle for me:

Shadowing real conversations beats isolated tone practice every time. I started following Chinese YouTube channels and podcasts, repeating after speakers while trying to match not just their tones, but their rhythm and intonation. This captured the natural tone changes and the way tones flow in actual speech, not the choppy, one-syllable-at-a-time way most practice materials present them.

Recording yourself is brutal but effective. I'd read simple dialogues, record them, then compare to native audio. The gaps were humbling but specific. I could hear that my third tones weren't dipping low enough, or that I was making second tones too dramatic.

Minimal pairs practice—but with context. Instead of drilling "mā má mǎ mà" in isolation, I practiced them in actual sentences where the meaning mattered. "我妈妈骑马吗?" (Is my mom riding a horse?) sounds silly, but it forced me to get each tone right or the sentence made no sense.

By the way, music actually did help me, but not how you'd expect. I didn't learn tones by singing Chinese songs. Instead, I learned to enunciate and get the sound of the words correct.

The Psychological Game-Changer

Here's something I wish someone had told me earlier: you don't need perfect tones to be understood. Context is incredibly powerful in Chinese. Even with wonky tones, people usually figure out what you mean.

I realized this during a conversation with my friend (house cleaner). My tones were all over the place, but he understood everything I said because the context made it clear.

This took so much pressure off. Instead of paralyzing myself trying to get every tone perfect, I focused on getting them "good enough" and letting context do some of the work. Paradoxically, this relaxation actually improved my tones because I wasn't so tense about getting them wrong.

Some Chinese friends disagree with this approach. My friend Xin insists that precise tones are crucial for sounding educated and professional. But my friend Hao says he rarely notices foreigners' tone mistakes unless they're really severe. As with many aspects of language learning, there's no universal Chinese opinion on how important tone perfection really is.

Regional Variations (The Plot Thickens)

Standard textbooks teach you Beijing-standard tones, but China is huge, and accents vary dramatically. What I learned in Chengdu sounded noticeably different from what I heard in Beijing.

Sichuan tones tend to be completely in a different order though there is still a relation. This is why listening in Chinese can be hard. Some regions have more neutral sounding neutral tones, others sound similar to the original tones.

This isn't to discourage you, standard tones will be understood everywhere. But it explains why the Chinese you hear in real life might not match your textbook recordings. When I first arrived in Sichuan, I worried my listening comprehension had suddenly gotten worse. Turns out, I just needed to adjust to the local accent.

The Long Game: How Tones Actually Click

Here's the truth no one tells you: there's usually a breakthrough moment when Chinese tones suddenly make sense, but it comes later than you expect and not through the method you're using when it happens.

For me, it happened after months of watching Chinese dramas and reality shows and then one day I was using Chinese tones the way Chinese people do, as part of the flow of communication rather than as isolated technical challenges.

That's when I understood: Chinese tones aren't a separate skill to master and then apply to speaking. They're integral to how Mandarin works, and they develop naturally as your overall Chinese improves, as long as you're getting regular exposure to native speech.

Common Plateau Points (And How to Push Through)

Most learners hit predictable walls with tone development:

The "Good Enough" Plateau: You can be understood most of the time, so you stop actively working on tones. I hit this around year three. My solution was to start paying attention to how different my Chinese sounded compared to natives in the same conversations.

The "Overthinking" Trap: You become so conscious of tones that your speech becomes robotic. I see this with a lot of intermediate learners. They speak slowly and deliberately, hitting each tone precisely but losing all natural rhythm. The fix? Practice speaking faster, accepting that some tones will be imperfect.

The "Regional Confusion" Phase: You start noticing that native speakers don't always follow the tone rules you learned. This is actually progress, your ear is becoming sophisticated enough to hear variations. Don't abandon the standard rules; just understand they're the foundation, not the ceiling.

What I'd Tell My Past Self

If I could go back and give my tone-struggling younger self some advice, here's what I'd say:

Start with natural speech patterns, not isolated syllables. Learn words in context, not as individual tone exercises. Don't worry about perfect pitch, worry about clear intention. Record yourself regularly, but don't expect overnight transformation. Most importantly, remember that tone mistakes are part of the learning process, not evidence that you're bad at Chinese.

The goal isn't to sound like a native speaker from day one. It's to steadily improve your ability to communicate clearly and naturally. Every mispronounced tone that leads to laughter or confusion is data; information about how Chinese actually works that you can't get from textbooks.

Some days you'll nail a difficult tone combination and feel like you're finally "getting it." Other days you'll mix up basic tones you've known for months and wonder if you're making any progress at all. Both experiences are normal and necessary parts of developing genuine tone competency.

Chinese tones aren't just a technical hurdle to overcome, they're a gateway into understanding how a tonal language organizes meaning and communication. Learning them well changes how you hear language itself, and that's a gift that extends far beyond just speaking better Chinese.

The journey is longer than most people expect, more interesting than textbooks make it sound, and absolutely worth the effort. Your future self, confidently navigating Chinese conversations without constantly worrying about whether you just said something embarrassing, will thank you for sticking with it.

If you want to get started with Chinese tones for the first time you can view our Chinese Tone Course it's got everything you need to get you started on a good foot.